Future of Museums: Playful Exercise Sparks Serious Questions

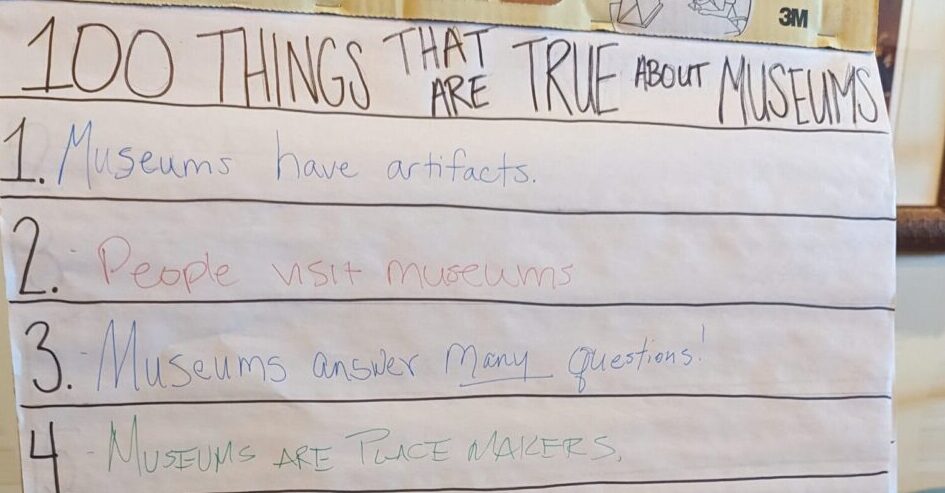

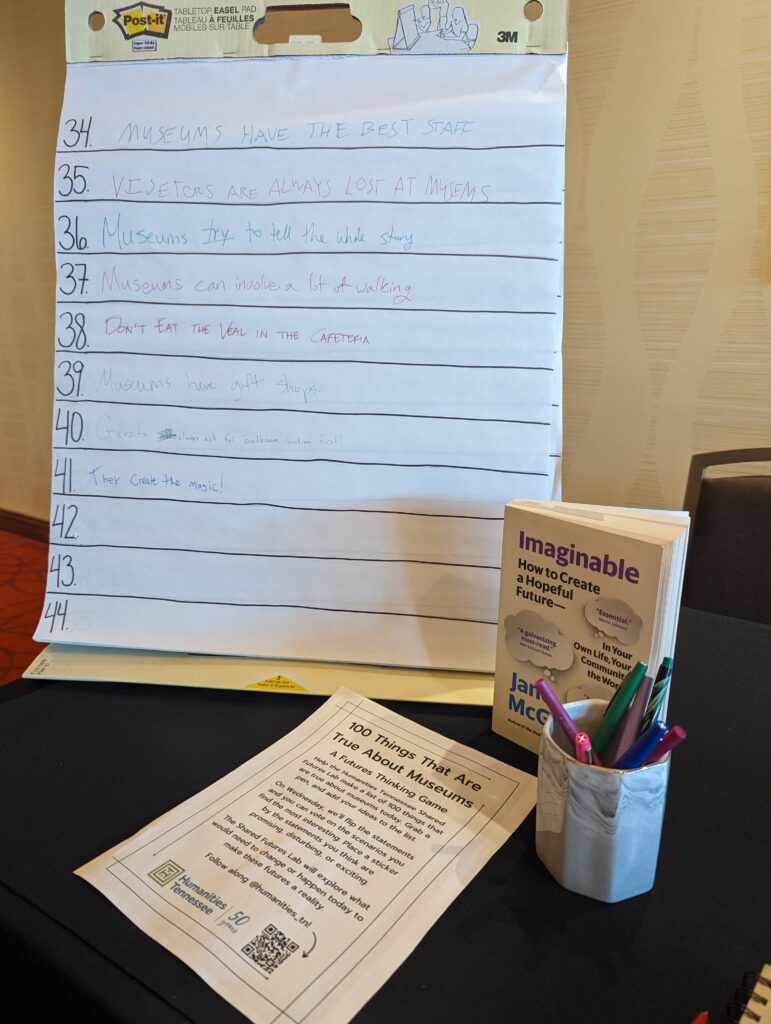

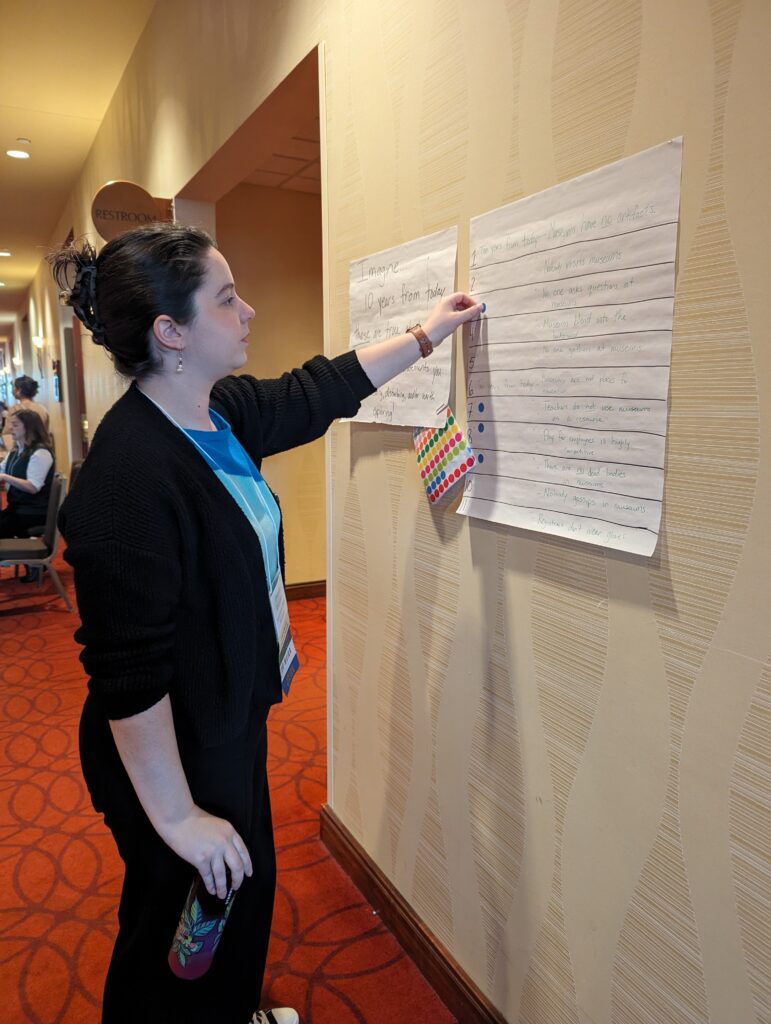

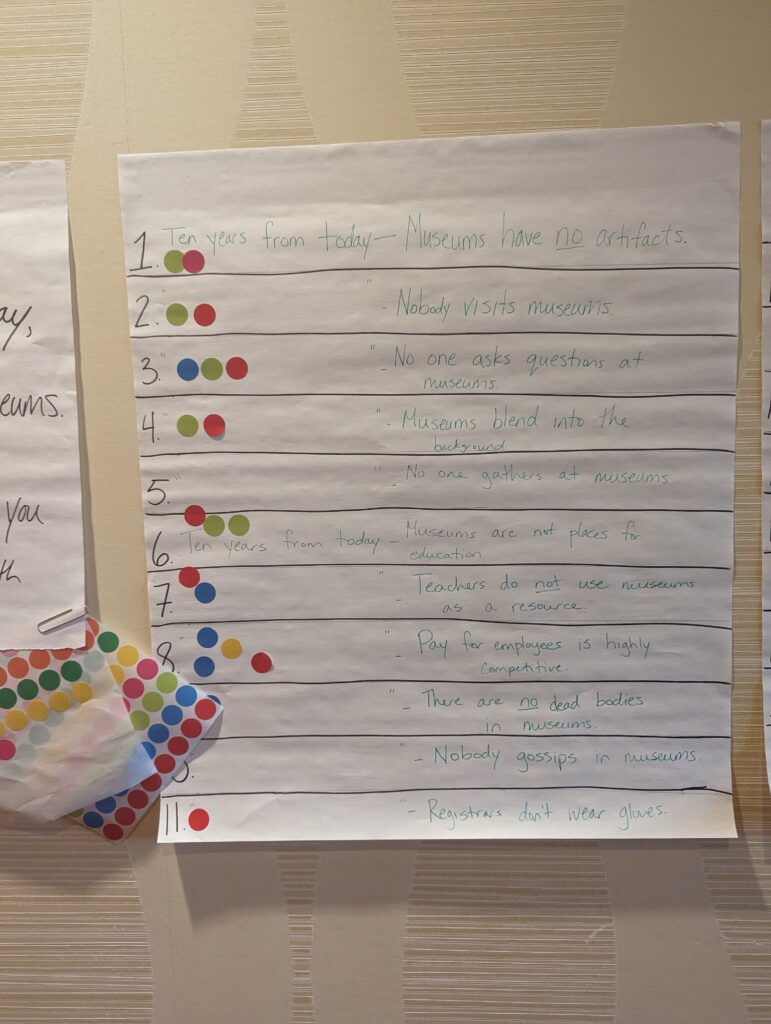

The Tennessee Association of Museums held its annual conference March 19-21, 2024, in Murfreesboro. Using giant sticky notes, felt tipped markers, and colored dots, HT’s Shared Futures Lab invited participants to play the futures thinking game 100 Things That Are True About Museums. Over the course of two days, we listed 55 things that are generally true about museums today. There were statements about museum hiring practices, educational missions, artifacts, visitors asking if buildings are haunted, and museums existing for their communities.

As the list grew, the Shared Futures Lab flipped the statements to imagine that ten years in the future, the opposite is true. “Most museum directors are white” became “Ten years from now, most museum directors are people of color.” And “Tourists love museums,” became “Ten years from now, tourists hate museums.” We cajoled everyone who walked by to place stickers next to the new statements that they found interesting, disturbing, or just worth exploring.

Among the hundred votes, three ridiculous – at first – futures emerged as being worth considering deeper. Futurists create scenarios by looking for evidence – or signals of change – that real disruptions or trends are already occurring that could conceivably lead to widespread adoption and change. With that in mind, let’s look to the present to see if and where our imagined futures are already lurking.

“Pay for employees is highly competitive.”

A May 2023 Museums Moving Forward survey found that over half of art museum workers make less than $50,000 annually. Three-quarters of those workers cannot always cover basic living expenses from their museum jobs, a finding which varied little across geographic locations. The majority (69%) of staff turnover at art museums over the survey’s calendar year occurred among employees making less than $50,000 annually.

In recent years, there have been localized efforts to increase the minimum wage from Tennessee’s legal requirement of $7.25 an hour (the national level set in 2009) to bring it closer to a living wage. In 2019, the City of Memphis made the minimum for its employees $15.50, which triggered city-operated museums to raise the pay of museum employees making less than that rate. Nationally, workers at more than 20 museums around the country unionized by May 2023, consistently citing wages, benefits, and working conditions as their main reasons.

Other related employment trends outside of the museum sector include companies and governments experimenting with four-day workweeks. There is also an increasing number of experiments with universal basic income – regular cash payments to all members of a community without conditions.

With these signals of change, we can imagine that in 2034, staff at museums across Tennessee have unionized and use collective bargaining to drive incremental increases in base pay as well as regular cost-of-living raises that keep pace with inflation. In local-government funded museums, staff have seen a regular increase in minimum wage requirements result in salaries in line with other professions. As a result, museums offer staff competitive pay and experience less staff turnover.

Imagine that you have just graduated from a museum studies program in 2036 and receive offers from three museums for entry-level jobs with a starting salary of $65,000. All the offers include three weeks of annual leave, four-day work weeks, retirement benefits, and health insurance. Now that compensation isn’t the prime consideration, what factors into your decision of which job to take?

“Museums are unsafe spaces [for ideas].”

The American Alliance of Museums’ report Museums and Trust 2021 found that trust in museums is based on perceptions of their presumed neutrality in being non-partisan and fact-based. The majority of respondents thought museums should be neutral on social and political issues. Today, proposed laws in several states and at the national level are raising questions about the role parents should have in their children’s education. Some of these laws deal with restrictions on school curricula, including limits on teaching about racism, sexuality, and gender. The accompanying debates are often extremely public and politically partisan.

Let’s imagine that Tennessee passes a Parents Right to Decide law in 2034. This act requires public schools to have a checklist on file for each student with explicit parental permission to teach topics including Black history, women’s studies, gender identity, and human sexuality. The checklists are binding on classroom teachers, school librarians, and proposed field trips. Museum administrators decide that they need school field trip revenue to continue operating. They remove programming and exhibit content that has topics related to the checklist to be in compliance.

Imagine you are chaperoning a field trip to a history museum and are required to attend a meeting at the museum before the students arrive. You are given a list of topics that you are not permitted to discuss with the students, or you will be told to leave the premises. You realize that you may not discuss slavery, immigration trends post-1970, or LGBTQ+ civil rights. What is the first thought you have? How does the list make you feel? What do you decide to do?

“The public considers museums essential.”

The same AAM report – Museums and Trust 2021 – found that people trust museums more than news agencies, the national government, businesses, and social media. The report concludes, “In a time when trust in most sources of information is declining, museums have proven resilient, retaining their “superpower of trust.”” These attitudes mean museums are excellent places to invite community members to have essential conversations and connect – or reconnect – outside of increasingly polarized environments and over politically-charged topics.

Imagine that you are attending your local museum’s regularly scheduled community conversation held the day after every political election, in this case the 2036 presidential election. These conversations are held in museums across the country and are considered an essential part of the election cycle. Each event follows the same format. Voters who supported the losing candidate are invited to share their fears about the newly elected representatives. Supporters of the winners then share what they are excited or hopeful the new representatives will do. The event ends with roundtable discussions. Imagine that your candidate lost. What fears do you share with the group? How does listening to your neighbors talk about their hopes change your opinions? When you leave the meeting, how do you feel?

Why think about the future of museums?

What value do these imagined scenarios about the future of museums provide to us today? Dr. Jane McGonigal points out in her book Imaginable, where this game originated, that “turning the world upside down can give you clarity about what you want to make different, in society and in your own life.” In other words, what scares us about the above futures is something we can actively work against now. And what makes us hopeful or excited are things we can take steps towards today.

What future do you want for Tennessee museums, as a visitor, volunteer, or employee? Tell us on Instagram or Facebook or send the Shared Futures Lab an email.