Exploring Southern Literature

Nearly 15 years ago, Humanities Tennessee launched Chapter16.org, an online literary publication created in response to disappearing book coverage in print and online media across the state. Since that time, Chapter 16 has built a loyal audience of readers and contributing writers. Through our website, weekly newsletter, and partnerships with four newspapers in TN’s major markets, new content in the form of book reviews, essays, Q&A sessions, poetry, and features are shared with more than a half million Tennessee readers annually.

In November 2020, Casey Cep authored a feature for The New Yorker titled “The Tennessee Solution to Disappearing Book Reviews.” This garnered us a national audience and as a result, likely new readers of Southern literature.

Perhaps new readers and long-time devotees of the genre contemplate what it means to engage with Southern literature? Or even how to define it as new voices and perspectives emerge. We wondered too!

So, we posed those questions, and more, to Chapter 16’s Editor, Maria Browning, and Kashif Andrew Graham, the first recipient of Humanities Tennessee’s Fellowship in Criticism for the publication.

HT: For you, what is the difference between reading and engaging with the written word?

Maria: Reading purely for entertainment, for the pleasure of getting lost in a story, is a lovely thing, but fully engaging with the written word is about so much more: an appreciation of the unique voice and craft that go into an unforgettable story or poem; the effort to see more deeply into a work to understand what it’s about — for the author and for you as a reader; and the connections you make between a given work and the many other works you know and love, so they commence a kind of dialogue in your mind. All these things are what you bring to the shared conversation about literature, whether that conversation takes the form of writing reviews or chatting with your friends.

Kashif: Well, I’m not certain that there is a difference—but it has to do with what I consider ‘reading’. Looking at the words is one thing. And plenty of people do that daily. What I suppose we would call engaging with the text is living in it for several pages, and then emerging to reassess the world around you. This may sound juvenile, but that’s because we learn this early in grade school. Our reading assignments and book reports ask us questions to this end. What did you read? What do you now think or feel? That’s engaging with the written word in a (very small) nutshell.

HT: What does it mean to you to engage with Southern literature?

Maria: I grew up steeped in 20th-century Southern literature — Faulkner and Welty and all the usual suspects. I did a semester-long independent study project on Flannery O’Connor at my Massachusetts college, even though I was not an English major. There was a much narrower understanding of what constituted the literature of the South back then. It wasn’t utterly homogeneous, but there was some sense, I think, that people like O’Connor and Ernest Gaines and even later writers like Jill McCorkle and Randall Kenan, each of whom had unique concerns, were all writing about a readily identifiable regional milieu.

We still have a regional literature, but it has expanded and evolved along with the region, becoming more urban and more culturally and ethnically diverse, while still being rooted in a sense of place and existing in dialogue — to varying degrees — with what marked the South and its literature historically.

Kashif: For me, engaging with the written word has to do with what I think and say. As a Southern critic, Southern literature is my gospel. It is my job to appraise this body of work on all sides. To ask what the creators are trying to do (and even whether that is a worthy cause) and to measure their success. I feel compelled to push Southern lit further—we have a unique opportunity and responsibility as the South is becoming something new. We are experiencing a reverse migration, where people from across the country are making homes in places like Nashville, Charlotte, Charleston, Knoxville, and Birmingham. Their presence will redefine the South. But they need to come home to something, to a tradition. Engaging is critiquing and creating, for me. I am also a writer whose focus is the new South. Moving in both offices means that my critique is tempered by understanding how difficult it can be to create.

HT: What do you think Southern literature offers and/or asks of its readers that is different than other genres?

Maria: It’s a great question — I do think the literature of the South continues to be deeply rooted overall in a sense of natural landscape. More than work from other places? I’m not sure I could prove it, but I think so, and as a reader, this is something I love. Read Charles Dodd White’s recent remarks in his C16 interview, and also Emily Choate’s amazing in-depth critical essay on this, which was one of the NEH Chairman’s grant-funded pieces: https://chapter16.org/among-the-pollinators/.

HT: What approach do you recommend for newcomers to Southern literature? …for readers who want to take a deep plunge into challenging Southern lit?

Kashif: Get a good mix of essays, fiction, poetry, and plays. I often consider essays to be the unfolding of fiction, and then another type of fiction themselves. Newcomers to Southern lit should start by debunking their ideas about the Old South. Too much of that obfuscates the colorblind racism that is a part of modern Southern society. I find that initiates to the genre are often in search of cotton and Jim Crow—without which, they don’t believe a piece could be about life in the American South. A collection of essays can disabuse newcomers of these superannuated visions.

And plays. Less reading and more seeing—but you must see When Boys Exhale by Anthony Green. It represents a melding of classical and the au courant. We are reminded that Black gay boys are an integral part of the modern South, too.

Maria’s recommended reading:

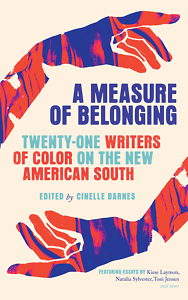

For me, it’s a wonderful thing to contemplate the work of writers like Anjali Enjeti or Neema Avashia as part of the current voice of the region. For thoughts from younger writers on this subject, see Kashif’s review of A Measure of Belonging, as well as the SFB session video with some of the writers in that anthology. Also, check out Brandon Taylor’s interview at Chapter 16, where he talks about his own sense of Southernness.

For me, it’s a wonderful thing to contemplate the work of writers like Anjali Enjeti or Neema Avashia as part of the current voice of the region. For thoughts from younger writers on this subject, see Kashif’s review of A Measure of Belonging, as well as the SFB session video with some of the writers in that anthology. Also, check out Brandon Taylor’s interview at Chapter 16, where he talks about his own sense of Southernness.

- I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood by Tiana Clark

- Lark Ascending by Silas House

- In The Valley by Ron Rash

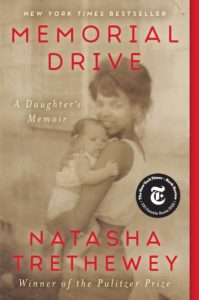

- Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey

- Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward

I already shared thoughts on essay and plays…and then there is fiction and poetry. Think more broadly, here. Does a book have to name a state in the South to be considered Southern fiction? The Black folks who fled the South during the Great Migration essentially created little Southern outposts in Harlem, Detroit, Chicago, Baltimore. Go Tell it on the Mountain by James Baldwin is a piece of Southern literature, even though it takes place in New York. But of course, other remarkable works do name the South, and should be read, including:

- A Measure of Belonging: Twenty-One Writers of Color on the New American South edited by Cinelle Barnes

- Long Division by Kiese Laymon

- The Trees by Percival Everett

- Love Child’s Hotbed of Occasional Poetry: Poems & Artifacts by Nikky Finney (my poetry mother!)

- Sinew 10 Years of Poetry in the Brew, 2011-2021 for poetry by people you likely brush shoulders with in the grocery store

In the first year after Chapter 16’s launch, Maria (as a contributing writer) interviewed Elizabeth Spencer, one of the South’s greatest writers. Spencer said, “As long as people live here in the South, I suppose they’re Southerners, and as long as they write about people living in the South, I suppose that’s Southern fiction.”

In the first year after Chapter 16’s launch, Maria (as a contributing writer) interviewed Elizabeth Spencer, one of the South’s greatest writers. Spencer said, “As long as people live here in the South, I suppose they’re Southerners, and as long as they write about people living in the South, I suppose that’s Southern fiction.”

Perhaps the next question to consider is “what do you think?”

We invite you to SUBSCRIBE to Chapter 16’s weekly newsletter for literary news and content delivered Monday mornings.

Maria Browning is a fifth-generation Tennessean who grew up in Erin and Nashville. Her work has appeared in Guernica, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Literary Hub, and The New York Times. She’s the editor of Chapter 16.

Kashif Andrew Graham was announced as the first Humanities Tennessee Fellow in Criticism for Chapter16.org. A freelance writer and librarian, Kashif is a frequent contributor to Nashville Scene, Chapter 16, Theological Librarianship, and other literary outlets. He has also appeared on C-SPAN, Queerology, and WPLN’s This is Nashville.

Kashif Andrew Graham was announced as the first Humanities Tennessee Fellow in Criticism for Chapter16.org. A freelance writer and librarian, Kashif is a frequent contributor to Nashville Scene, Chapter 16, Theological Librarianship, and other literary outlets. He has also appeared on C-SPAN, Queerology, and WPLN’s This is Nashville.