Sharing the Untold Story of Tennessee’s Enslaved Iron Workers

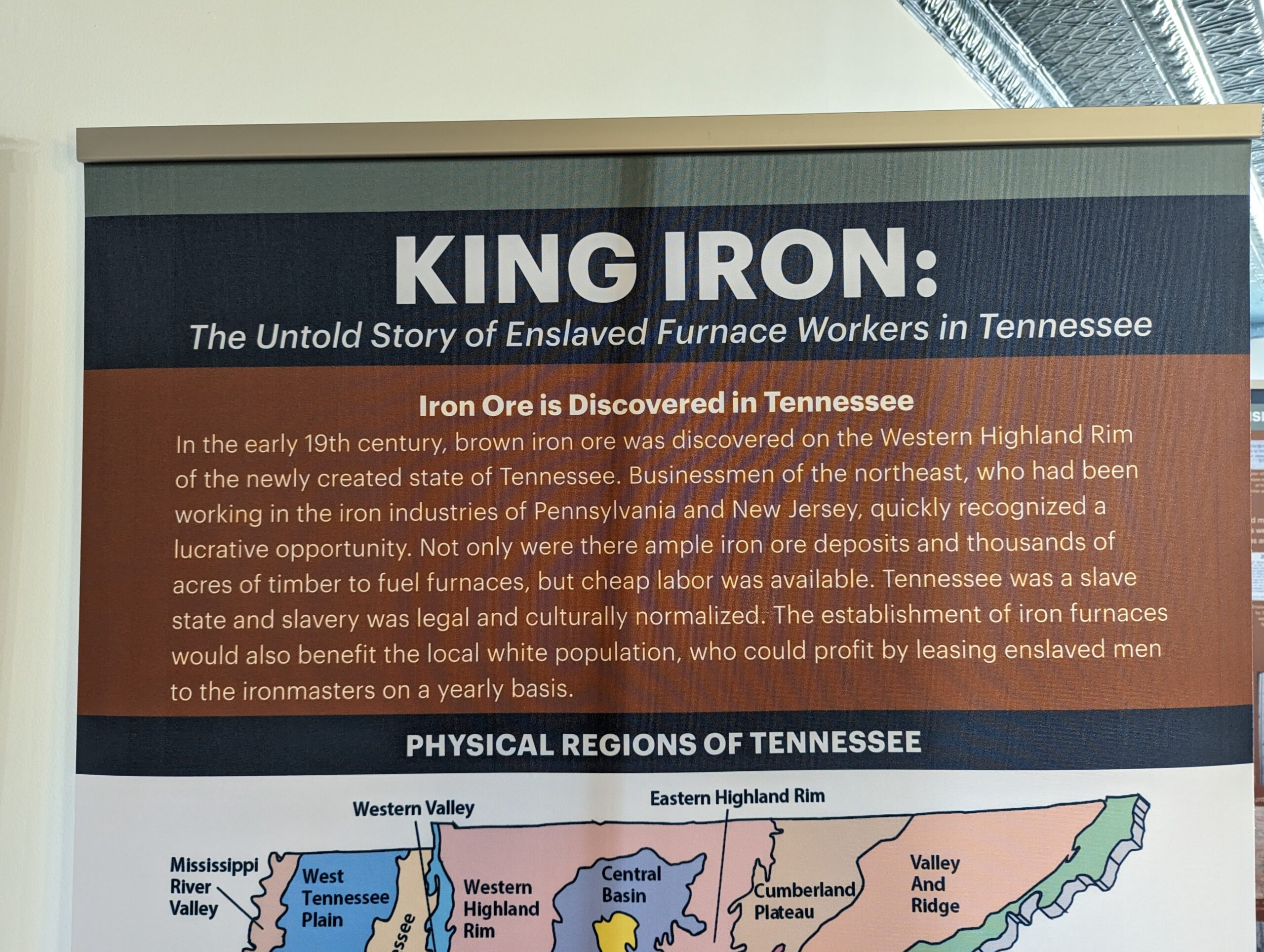

Human enslavement in the American South prior to the Civil War is well-documented as a brutal system of extracted and uncompensated labor. When most of us consider enslavement in Tennessee, we tend to think about enslaved workers on agricultural plantations cultivating, harvesting, and processing cotton, tobacco, grain, and cattle. However, industrial enslavement was a main economic driver in Middle Tennessee. The experiences of these enslaved men and boys are the subject of The Tennessee African American Historical Group’s (TAAHG) new traveling exhibit, King Iron: The Untold Story of Enslaved Furnace Workers in Tennessee, which was partially funded by a grant from Humanities Tennessee.

The Exhibit

King Iron centers the lived experiences of enslaved workers in Middle Tennessee’s iron industry by focusing on the workers’ skill, daily lives, and attempts at freedom. The Middle Tennessee region sits atop limestone and shale with significant iron-bearing ore deposits. The discovery of these deposits in the early 1800s along with the acres of timber needed to fuel furnaces and the availability of cheap, leasable, enslaved Black labor led to iron becoming a major economic driver in the region. Well-known historical figures including James Robertson, one of the founders of Nashville, and Montgomery Bell made fortunes as iron furnace owners.

In addition to text panels, the exhibit includes artifacts from furnace sites and a diorama of a working iron furnace. Some of the panels detail what Tracy Jepson, TAAHG’s Historian and one of the exhibit’s co-curators, describes as “really hard history,” including the beheading of Henry King, the leader of a planned though unsuccessful insurrection among the iron workers, in Dover, Tennessee. Frederick Murphy, TAAHG’s President, exhibit co-curator, and founder of History Before Us, says, “we want people to understand how brutal the iron furnace industry was. These folks who worked 12 to 16 hours, seven days out of the week…a lot of these men didn’t live over 50 years old because of just being brutally worked to death.”

The exhibit culminates with a consideration of ironworkers’ lives after enslavement. Some workers emancipated themselves, joined the Union’s United States Colored Troops, and fought in the Civil War. After the war, former enslavers hired furnace workers as paid employees, but exploitative labor practices continued. However, as the exhibit concludes, emancipated iron workers “went on to create new communities, fulfilling their lifelong dreams of dignity and independence.”

Descendant Community

For Murphy, this exhibit is personal. He knew that his great-grandfather was employed at Cumberland Furnace, but it wasn’t until doing archival research that he discovered that he is a descendant of enslaved iron workers. In 2021, Murphy and another descendant of their shared ancestor Ferdinand Jackson went to the plantation in Alabama where he was enslaved. Two years later, Murphy was looking through the “Negro Book” from Louisa Furnace in Montgomery County, Tennessee, and found Jackson listed. He had been leased from the Alabama plantation to the Tennessee iron furnace for thirty years.

Murphy recalled, “It was just powerful when I turned that page, and boom, it was right there – Ferdinand Jackson. You get this feeling…it’s kind of eerie…it’s radio silence for a moment and then [I] just sat back and got back to it. It was surreal.”

Why This Story Matters Today

For Jepson, it is important to share this story today because “healing begins with remembering…we can’t really move forward and be whole until we fully sit with the whole story.” It’s also a matter of representation. One of TAAHG’s first projects was getting historical markers specifically about Black history in the Clarksville area, including one on the site of the city’s slave market. This exhibit is another way to expand the stories being told about the region to ensure that they reflect the experiences of the entire area’s historic populations.

For Murphy “It’s important to tell [this story] today not just so our youth can know about how expansive the institution of slavery [was], but also adults. There’s still people in my community…that didn’t have a clue about the iron furnaces because it’s just not talked about.”

This exhibit highlights the humanity of the enslaved workers as well as the fact that their descendants are still plentiful in the region today. TAAHG started a Facebook page “to celebrate and acknowledge African American History in the counties of Montgomery/Dickson County, TN & Hopkinsville, KY.” This growing community shares archival materials and oral histories to uncover the past and discover family connections. Through this work, more individuals are discovering their ancestors’ connections to the iron furnace industry.

To this end, Murphy welcomes “any conversation…to share information to make all of our histories more comprehensive and [to get] a better understanding of how collaborative work can really fill the gap for not only the African American descendants but for the descendants of the enslavers as well.”

A Future Full of Representation

When Jepson imagines Tennessee two decades from now, she “wants the full [history] to be out there and normalized.” In her vision for the future, “[Representation] has been there so much as part of the landscape – minority groups, women’s history, Black history, LGBTQ history, all of that together – that people expect that variety to be there. They’re used to it. It’s soaked in. And without even hardly realizing it, that full narrative is just part of their consciousness.”

For his part, Murphy says, “I love home…I also understand the challenges that we have in Tennessee, but there’s also a lot of good things that are happening. My hope is that individuals are able to see how humanistic-centered programs can really change the narrative of the state, by storytelling, by coming to the table with people that do not look like you. Harnessing how diverse our history is, how diverse our [present] is right now, and how diverse the future will definitely continue to be [is] the only way…to create some sense of comfortability…through conversation and through better understanding.”

Join the conversation!

- What are your thoughts on this often-overlooked chapter of Tennessee history?

- Do you have ancestors connected to the iron industry?