How to Sue the Klan: A Story of Resilience and Justice

In late April 1980, racially-motivated violence changed the lives of five Black women in Chattanooga. A local Ku Klux Klan leader driving two other Klansmen fired through their car’s open window, striking four of the women with bullets and injuring the fifth with flying glass. In the subsequent criminal trial, an all-white jury acquitted two of the men and sentenced the third to a $50 fine and nine months in jail, of which he served six.

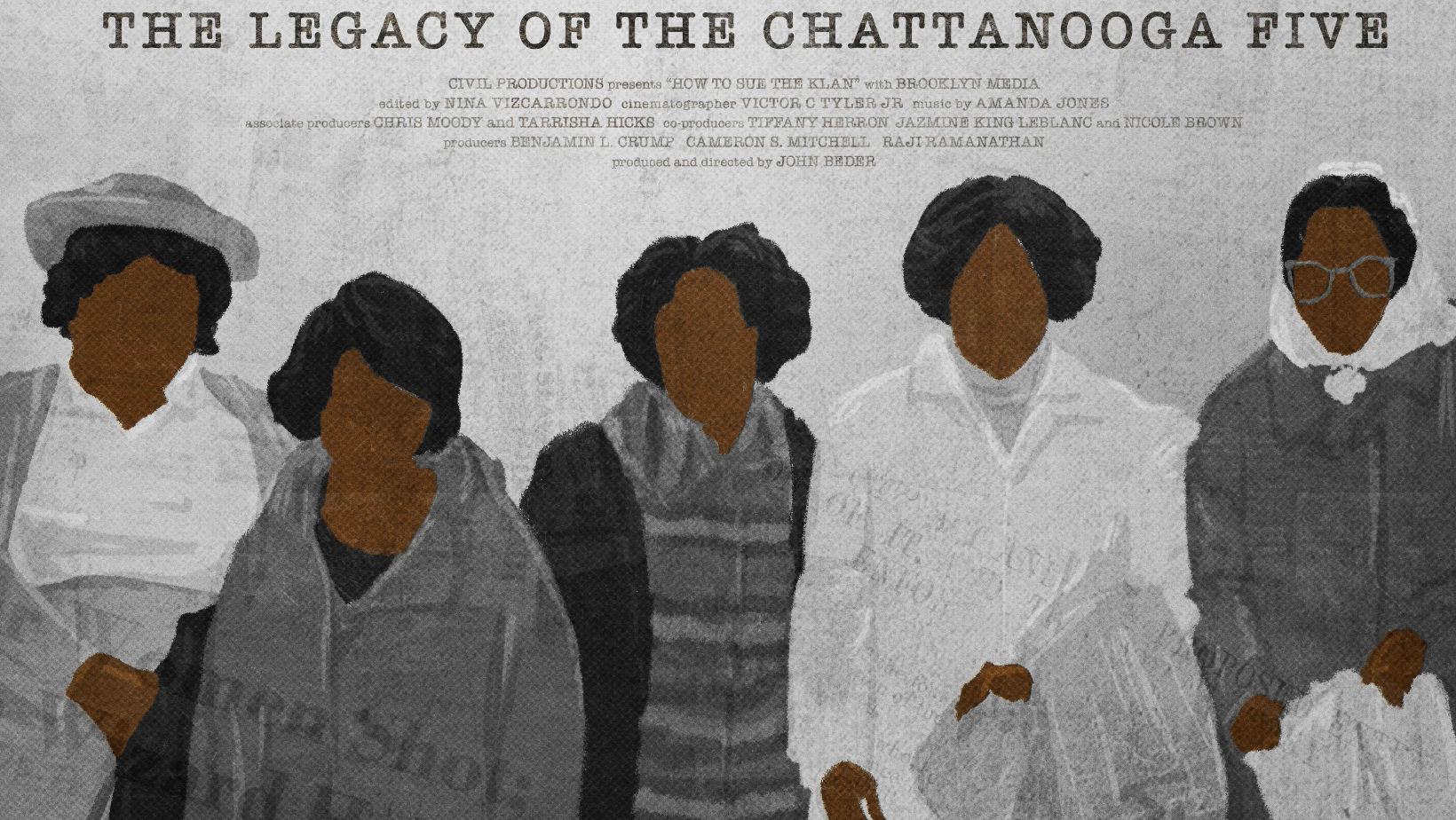

This unrealized attempt at justice for Fannie Mae Crumsey, Viola Ellison, Lela Mae Evans, Opal Lee Jackson, and Katherine Johnson could easily have been the end of the story. Instead, the chronicle of their successful civil case (Crumsey v. Justice Knights of the Ku Klux Klan) is the subject of the new documentary How to Sue the Klan by director John Beder, which was partially funded by a grant from Humanities Tennessee.

Preserving Fading History

Beder, a Chattanooga filmmaker and co-owner of Bedrock Productions, makes documentaries that focus on challenging topics while centering the humanity of the people sharing their stories. For Beder, a documentary film about the civil trial was a timely decision. “We could see elements of this 40-year-old story being forgotten and missed with each passing year…A documentary could help preserve this fading piece of history and also bring it the attention it deserves.” How to Sue the Klan traces the history of the trial while also exploring its contemporary legacy.

After the unsatisfying criminal trial, the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) in New York City filed a lawsuit against the Ku Klux Klan in federal civil court on behalf of the women. According to Professor Randolph McLaughlin, the lead attorney on Crumsey, the CCR was looking for a test case to create a legal remedy for racially motivated violence, incidents of which were on the rise in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

McLaughlin and his team successfully used the 1871 Ku Klux Klan Enforcement Act to argue that the Chattanooga women were owed compensation. President Ulysses S. Grant signed this law in the aftermath of the Civil War to allow survivors of Klan violence to sue for damages in civil court when criminal charges failed. Prior to the Crumsey case, the law had never been tested in court.

Ultimately, the court awarded the plaintiffs $535,000 in damages and served the Klan an injunction prohibiting them from entering the Black community and engaging in violence in Chattanooga. The victory was clear and decisive, but it was one that was not memorialized.

A Critical Tool for the Present

For McLaughlin, the use of a Reconstruction era anti-Klan law in this case “felt revolutionary.” It is also an aspect of this history that is a critical tool today. As the documentary reveals, lawyers around the country have used the Crumsey case as precedent over the past four decades. The case remains a model for civil rights attorneys who have used the statute to sue for civil damages in the aftermath of the attacks in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the January 6th insurrection in the U.S. Capitol among others.

For Beder, the importance of this film today cannot be overstated. He noted, “While we wish America wasn’t in need of another history lesson from our violent past, we are once again witnessing white supremacists committing acts of racially motivated violence. Through the process of making this film, we’ve realized the lack of civil rights lawyers and resources available for cases like this to still be pursued. We believe this film will not only inspire those who’ve forgotten, but also those who can use this information to pursue their own cases against hate groups.”

A Future Legacy

One thing McLaughlin imagines for the future is a memorial to these women in the public park across the street from the courthouse to celebrate the site of their victory. He remembers a Depression-era mural titled Allegory of Chattanooga that hangs behind the judge’s bench in the federal courthouse. As he describes it, “In the center of the image is a beautiful white woman in a bonnet holding a white baby in her arms. To one side you see Confederate soldiers coming back from the war. On the other side, you see Black people picking cotton…I’m trying a case involving the Ku Klux Klan in that courthouse facing that image.” A future monument that honors the legacy of the Chattanooga Five in preventing future acts of Klan violence across the street from the building that houses that image would tell a more complete and balanced history of the city.

Participating in this documentary was a full circle moment for McLaughlin. He wants students to be inspired by How to Sue the Klan in the same way that he was inspired to enter into civil rights law after seeing The Chicago Conspiracy Trial. The film is how he came to know William Kunstler, the Chicago 7’s defense attorney and co-founder of CCR. As McLaughlin said, “I’m [Kunstler’s] legacy. I want these students to be mine, so that they’ll be inspired to do the work that needs to be done. I can’t do it all. None of us can, but collectively, we can move mountains.”

Interested in seeing How to Sue the Klan? Visit the documentary’s website to find a list of upcoming screenings or to book your own.