McClung Museum Reimagines Future by Centering Native Voices

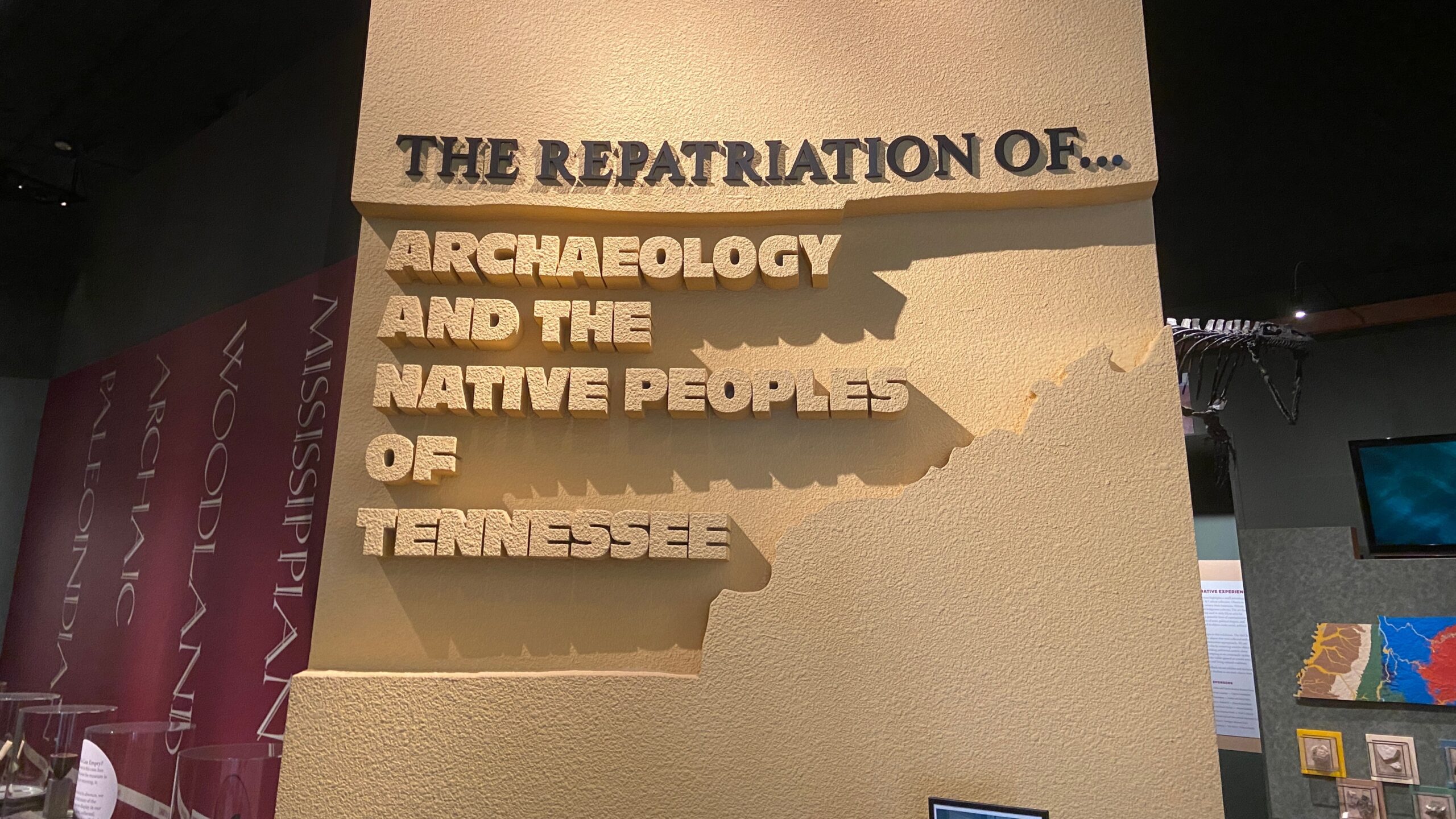

In 2000, a new permanent exhibit – Archaeology and the Native Peoples of Tennessee – opened at the McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture on the University of Tennessee, Knoxville campus. Museum curators organized the exhibit using an archaeological time scale, emphasizing material culture taken from earthen, monumental mound sites. A member of the American Alliance of Museums’ accreditation team called the exhibit, which Humanities Tennessee partially funded, “a quantum leap forward…[that will] stand as an example to emulate by other museums in the country.”

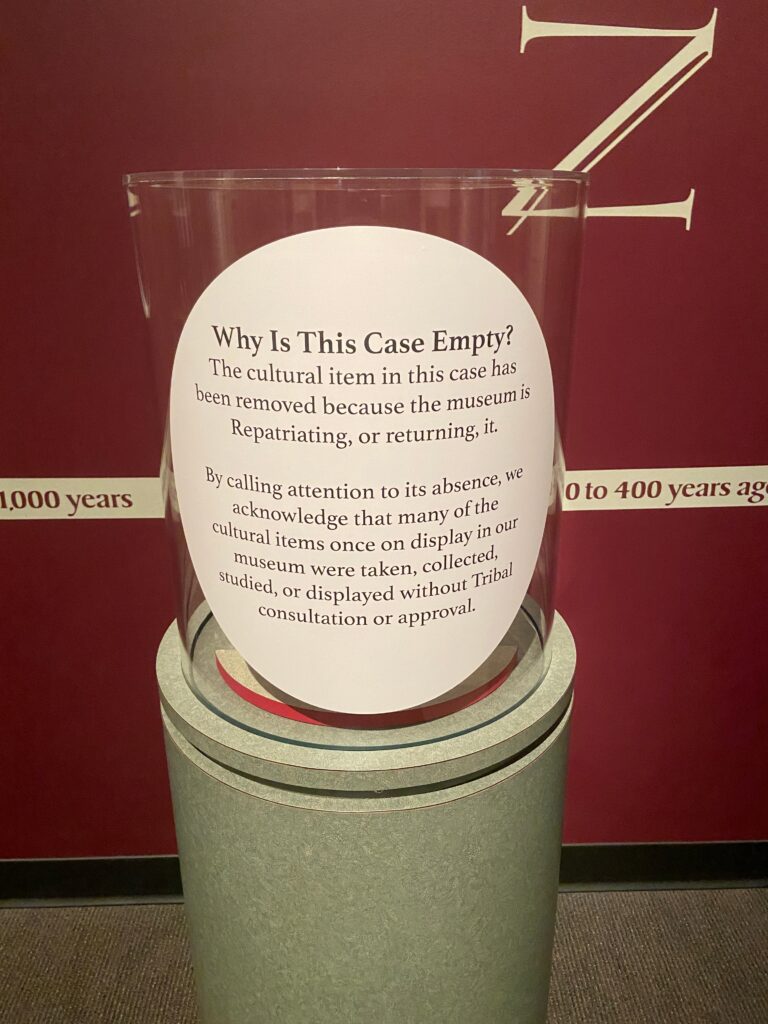

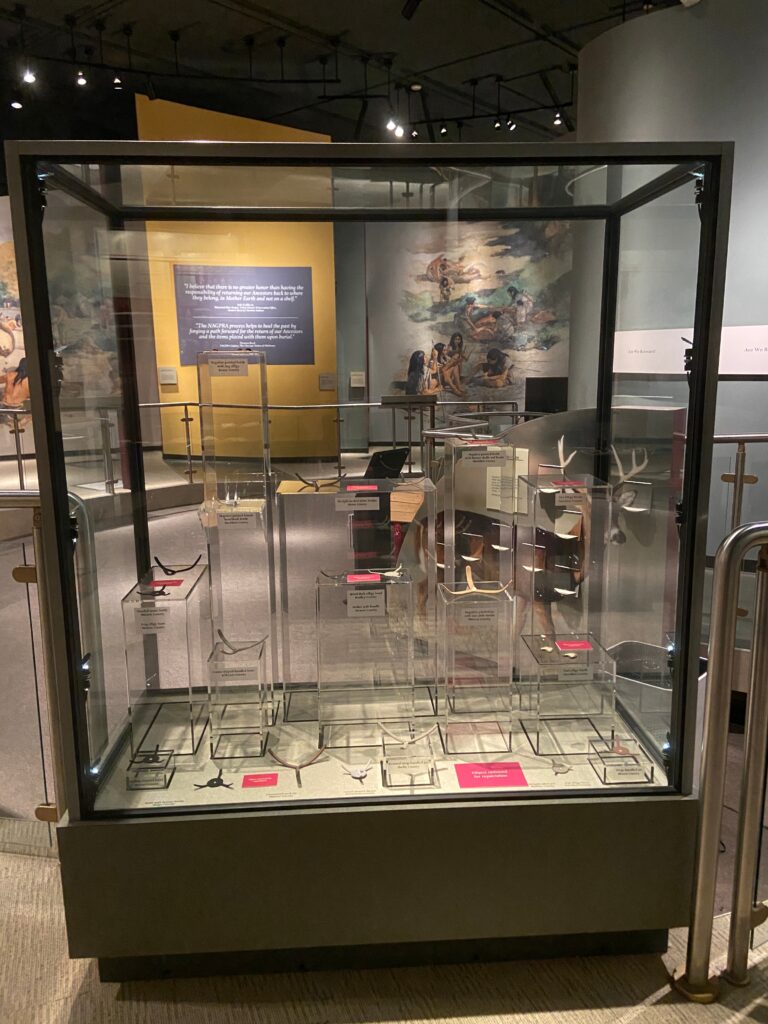

Twenty years later, Humanities Tennessee awarded the McClung a SHARP grant, a funding program for projects to support long term COVID-19 recovery, sustainability, and equity. The McClung used the grant to create a new strategic plan. Two of the resulting objectives are to “build new and strengthen old relationships with Native Nations,” and “prioritize repatriation compliance and consultation” for materials in their care. As a result of the subsequent formal consultation process, the staff, in collaboration with Native partners, created a temporary intervention over the Archaeology exhibit. They removed Belongings, left cases empty, and added new interpretive labels. After a successful run, they dismantled the gallery in January 2024 to begin construction on a new exhibit co-curated with Native partners that will be a radical departure from the organization, tone, and content of the previous one.

Why is this change so critical to the McClung Museum? And what can it tell us about the future of voluntary repatriation in museums?

An Ethical Intervention

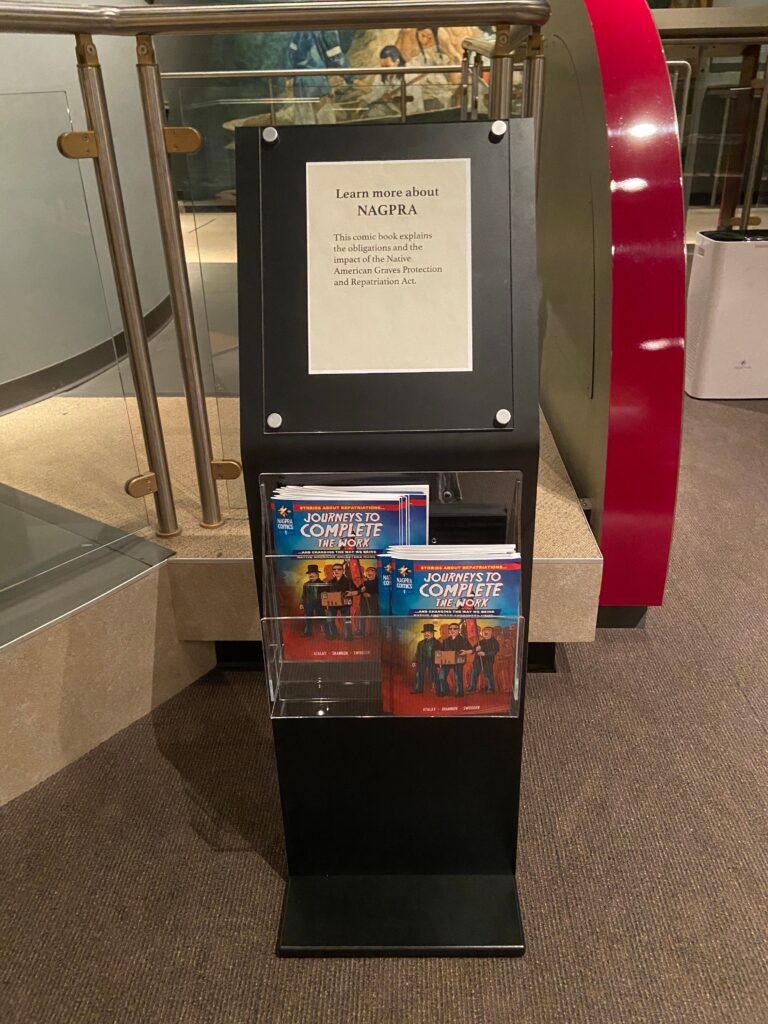

The McClung Museum, like all institutions receiving federal funding, must comply with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed by Congress in 1990. This law outlines when and how museums must repatriate – return – Native American Ancestral Remains and sacred, burial and patrimonial materials to affiliated Tribes.1

In line with their new strategic plan, McClung curators began formal NAGPRA consultations with Tribes who did not want Belongings to remain on display during the repatriation process. Staff pulled about a quarter of the Archaeology exhibit off of display.2 Cat Shteynberg, Assistant Director and Curator of Arts & Culture Collections, explained, “At that point, we had the choice of either sun setting gallery and not being transparent about what was happening or to tell the story of why [this] was happening and what NAGPRA is.”

The temporary black and white panels installed over the existing casework explained what NAGPRA requires, invited visitors to think about who is telling the story, and called attention to empty cases to acknowledge that the items previously on display were there without Tribal consultation or permission.

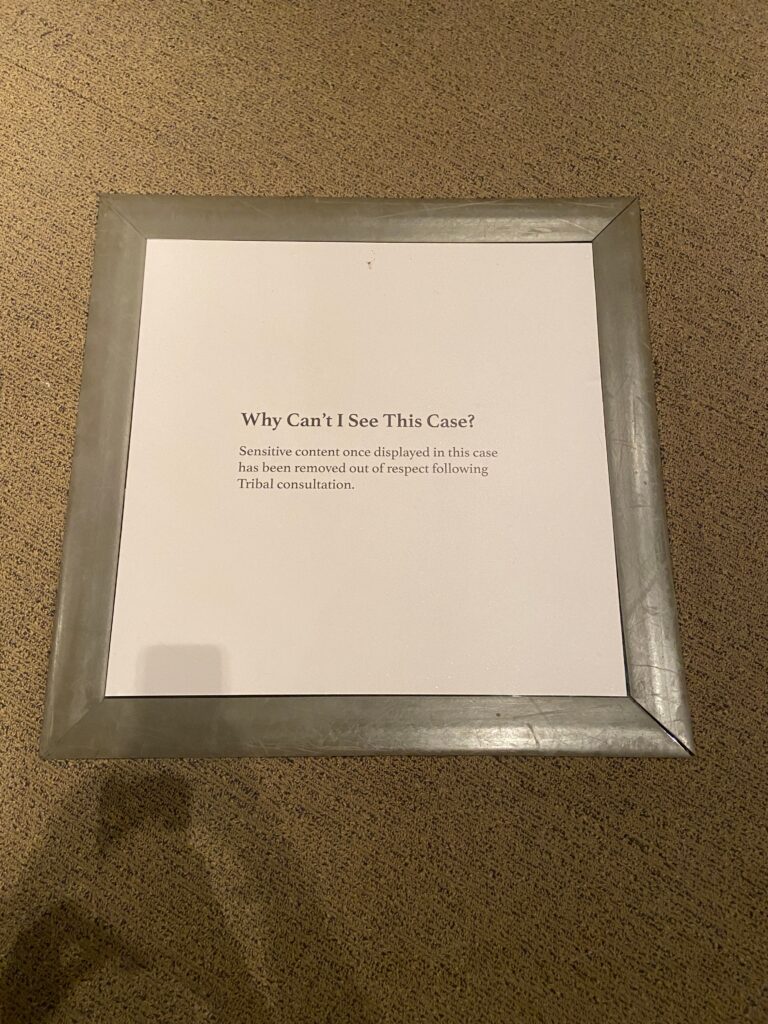

The intervention went beyond the removed objects to consider what stories non-Tribal members have a right to know, even if that knowledge was previously available in the museum. For example, the original exhibit included a reproduction of a dog burial; however, as Curatorial Project Manager Sadie Counts said, “the burial knowledge is not knowledge we can share. So even though this is a facsimile, it still references original knowledge that we [the museum] weren’t supposed to be sharing.” Staff covered the display, which was inside a case set into the floor, with the explanation reading, “Sensitive content once displayed in this case has been removed out of respect following Tribal consultation.”

New Exhibit Points toward Future Ways of Curating

The intervention closed in December 2023 for renovations to the gallery. Museum staff and eleven Native Co-Curators are currently planning Homelands: Connecting to Mounds through Sacred Art, an exhibit that will explore Native Tribes’ connections to sacred landscapes through contemporary Native art, which will open in 2025. According to Shteynberg, “when people think about mounds, they only think about the ancient past, even though they’re living and important today. These communities are still here…so it was very pointed to only have contemporary art in the space.”

Every element of the new design is going through caucus review, which is a radical departure from the way the museum has previously curated exhibits. This decision-making process ensures that the voices, experiences, and opinions of the co-curators are centered throughout all aspects of the exhibit. In terms of design, for example, the museum is removing the in-floor cases because of the strong negative feelings their partners have about walking on Belongings and material culture.

Looking further ahead for this gallery, McClung staff are considering an exhibit about the human and non-human lifeways of the Tennessee River, which runs just south of the museum. Among the curatorial issues they are considering from even this early phase is how to give equal voice to UT scholars, Native Tribes, and museum curators to tell a complete story of the river that builds on the relationships they are cultivating.

Counts explains that “as a museum of natural history and culture, we have these four distinct collections [that] we’re trying to bring together in this exhibition. It’s a really exciting opportunity to think about all of our collections in conversation with one another.” Combining collections and ways of knowing into an exhibit that obscures the line between science and culture will be yet another departure for the museum, but one that has the potential to create a story that resonates with all of the museum’s communities.

A Heart-Centered Future

When asked to consider the McClung Museum’s future, Shteynberg noted that being open to not knowing what will change is important. But, she said, “I’ll know that the work is important because it will make me nervous. I think that our work should make us a little bit nervous because it pushes us into new territory that we didn’t know was even there.” Counts concurred, adding that “we at the museum have to anticipate that we will change in ways we can never know until we get there.”

For both curators, the future of this museum will involve deep listening, accountability, and a willingness to sit with uncertainty. As Shteynberg said, their “work has to be heart-centered and centered in kindness. If you’re truly engaging with a partner, if you’re truly engaging with your audience…and you’re really listening and not just telling, you will be doing good work.”

- A note on terminology: NAGPRA uses the phrase ‘funerary objects’ to describe materials buried with human remains. The McClung Museum says ‘Belongings’ after consultation with Native partners. Similarly, the museum says ‘Ancestors’ instead of ‘human remains.’ ↩︎

- The updated NAGPRA regulations that went into effect in January 2024 now mandate the removal of Ancestors and Belongings from display unless the museum has the explicit consent of Native Nations. The McClung Museum’s intervention took place before these changes went into effect. Their activities went beyond compliance with the law. ↩︎

The McClung Museum provided photographs of the intervention for this post.

Join the conversation!

- What do you think of the McClung Museum’s transformation?

- How can we ensure all communities have a voice in shaping our future?

- What role can museums play in creating a more equitable society?